The Historic Houses of Richard H. Jenrette, Part II: The Interiors and Furnishings

Author: Grant Quertermous

Want to learn more?

In addition to assembling an impressive collection of historic houses, Jenrette developed a reputation as a knowledgeable collector of American decorative arts, especially Classical New York furniture.

However, he didn’t see this collection of furniture by cabinetmakers such as Duncan Phyfe and Charles-Honore Lannuier as stanchioned-off museum pieces but rather objects that should be used in much the same way it had been used for the past two centuries. He surrounded himself with his collection, furnishing his bedrooms at many of the houses with a Duncan Phyfe bed, or taking meals in a Dining Room furnished with a Duncan Phyfe dining table and chairs. For Jenrette, his houses and collection had an interrelated and complementary relationship.

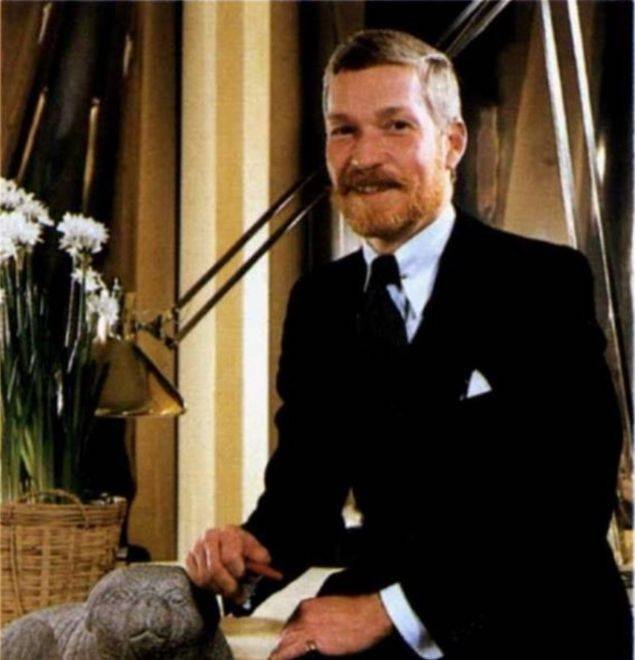

Jenrette and his partner, William L. (Bill) Thompson at Edgewater, 1970. Jenrette Foundation Collection

One individual who played an especially prominent role in the decoration and furnishing of the houses discussed in this article was Jenrette’s best friend and partner of forty-eight years, William L. Thompson. He researched the history of the properties and helped to locate original furnishings and portraits. Antiquing was also a favorite pastime for Jenrette and Thompson and a source for many of the objects used to furnish the homes. For some of the later properties, Thompson even designed bed hangings, carpets, and window treatments.

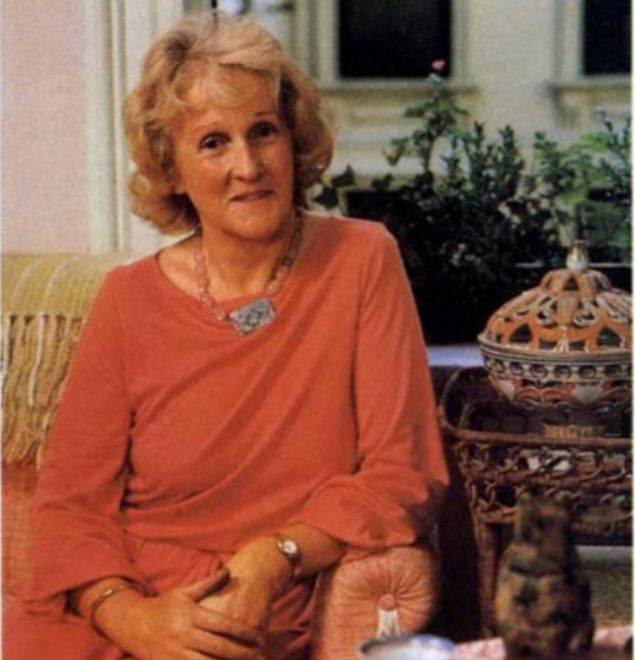

North Carolina-based designer Otto Zenke

Courtesy Greensboro News & Record

Jenrette’s first Manhattan real estate purchase in the early 1960s was a co-op apartment located in a pre-war building at 455 E. 57th Street. After visiting the apartment, a colleague suggested that Jenrette hire North Carolina-based designer Otto Zenke (1904-1984) to decorate the apartment. “This turned out,” as Jenrette later wrote, “to be an inspired decision.” Born in Brooklyn in 1904, Zenke had studied interior design at the Pratt Institute and Parsons School of Design and began his career at B. Altman & Co. After establishing himself as a designer, Zenke had moved to Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1937, where he worked as chief decorator for the Morrison-Neese Furniture Company. In 1950, he opened Otto Zenke, Inc., in partnership with his brother Henry Zenke. The firm eventually expanded to eventually include offices in Palm Beach, Florida, and London, England. When Jenrette moved to Europe for two years while he worked to establish DLJ’s continental presence, he rented a Belgian farmhouse near and hired Zenke to decorate and furnish it.

Advertisement for Otto Zenke Interiors, c. 1970

Jenrette Foundation Collection

“Designing an interior is a matter of understanding and expressing the personality of a client,” Zenke told Architectural Digest in 1973. As Jenrette later recalled in Adventures With Old Houses, hallmarks of Zenke interiors included late Georgian and English Regency antique furniture, ample upholstered chairs and sofas, and lamps spread throughout a room. Jenrette also noted the designer’s long-lasting influence in the way he approached the furnishing and decorating of his houses such as letting a fireplace flanked by tall bookcases serve as a focal point of a room.

In 1968, Jenrette purchased Roper House, a c. 1838 house on Charleston’s High Battery. While not his first piece of Charleston real estate, it would be the house that he would restore and enjoy for the rest of his life. He later wrote that it was his purchase of Roper House that enhanced his “appreciation of the value and importance of historic preservation,” which in turn led him to create Classical American Homes Preservation Trust in 1993. In addition to its builders, Robert William Roper and his wife Martha Rutledge Laurens Roper, previous owners included members of the prominent Allston, Ravenel, and Siegling families, as well the modern art collector and businessman, Solomon R. Guggenheim.

Roper House, completed in 1839, is located on Charleston’s High Battery

As part of Jenrette’s purchase agreement of Roper House, the previous owner’s widowed mother was given a life tenancy of the second floor. Jenrette and Thompson occupied the third floor and added a roof-top deck that offered a prime location for sunset cocktails. For the decoration of these third-floor spaces, Jenrette hired San Francisco designer Anthony Hail (1924-2006), whom he had met thought a Harvard Business School classmate. Hail, whose design career spanned nearly fifty years, was named by Architectural Digest’s Mitchell Owens as one of “The 25 Most Influential Interior Designers of the 20th Century.” In addition to Roper House, Hail also served as interior designer of the Mills House Hotel, the reconstruction of the iconic Charleston hotel led by Jenrette that opened in 1970.

Designer Anthony Hail, 1969

Jenrette Foundation Collection

Born in Houston, Texas, Anthony Hail grew up in Denmark where his stepfather was in business. He later returned to the United States and attended Harvard Graduate School of Design. Hail moved to San Francisco in the 1950s to open his own design firm while also writing for various magazines. House Beautiful’s Jennifer Bowles called Hail the “éminence grise of the San Francisco design community.” He credited his time in San Francisco with influencing his design aesthetic, which focused on blending Chinese decorative arts with British and Continental European antiques within the same space.

Jenrette later wrote that Anthony Hail, “got me out of the rut of thinking that everything had to be late-eighteenth century English Georgian.” At Hail’s suggestion, Jenrette began acquiring French mantels, 18th and 19th century Scandinavian furniture, antique Russian chandeliers, and Chinese porcelain.

Surviving images of the third-floor spaces at Roper House during this era show rooms that were furnished with antique British mahogany furniture and Asian decorative arts, including a large japanned twelve-panel Coromandel screen which served as the focal point of Jenrette’s third floor sitting room.

While Roper served primarily as a weekend house, Jenrette also acquired a c. 1840 Greek Revival townhouse in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village in 1969 to serve as his principal residence. Jenrette only occupied the first floor but enjoyed the large windows and fourteen-foot ceilings. Anthony Hail was again hired as decorator. Extant invoices and correspondence from the designer in the Jenrette Foundation’s archives suggest that the house was furnished with an eclectic variety of décor, including bamboo chairs, a pair of standing brass lamps, a painting by the 18th century French painter Jean-Baptiste Oudry, and antique Chinese lacquer tables.

Edgewater

When Jenrette purchased Edgewater from the writer Gore Vidal in the fall of 1969, Anthony Hail was also responsible for the interiors. Images in the Jenrette Foundation archives of Edgewater’s Drawing Room during this era show that the walls were painted a vibrant yellow and the space was furnished with Asian and Continental European antiques, Chippendale mirrors, marble-topped console tables, and English regency furniture.

Jenrette's salon at 150 E. 38th Street, New York

In the fall of 1970, Jenrette moved from Greenwich Village into a circa 1858 house on East 38th Street that he purchased from publisher Cass Canfield. The three-story house had double parlors on the first floor and bedrooms on the second and third floors. A second-floor room which spanned the full width of the house served as Jenrette’s library and office. For this house, Hail created what Jenrette described as a “Louis XVI-style salon,” transforming the front parlor into a space out of the Petit Trianon with antique French furniture and works of art.

The drawing room at 1 Sutton Place

After owning the East 38th Street house for two years, Jenrette purchased a townhouse at 1 Sutton Place in 1972. The neo-Georgian townhouse was designed in 1921 by architect Mott Schmidt for Anne Harriman Vanderbilt, the widowed second wife of William K. Vanderbilt, and a later owner was Merrill Lynch co-founder, Charles Merrill. To complement the architectural style of the house, Jenrette decided that he wanted a distinctly British look for the interiors, so he called New York designers Harrison Cultra (1941-1983) and Georgina Fairholme (1927-2019) for a “quick fix on this grand English-style Georgian house.”

Harrison Cultra, 1984

Courtesy Architectural Digest

Cultra had been named a “rising young star” of the design world by The New York Times shortly before he and Fairholme were hired for the Sutton Place project. However, his career was ultimately cut short by his untimely death in 1983, at age 42. Born in Urbana, Illinois, he attended the University of Arizona and studied Fine Art at the Sorbonne in Paris. Prior to going into partnership with Georgina Fairholme, he worked in the Madison Avenue showroom of designer Rose Stuart Cumming (1887-1968).

With his partner Richard Barker, Cultra spent three years restoring Teviotdale, his 18th century Livingston family house in the Hudson River Valley. Cultra also gained recognition for his work on the inaugural Kips Bay Decorator Showhouse in 1973. In his 1983 New York Times obituary, the editor of Architectural Digest, Paige Rense, remarked that Cultra was “traditional, with great style,” and that he “knew antiques very well, but his color palette was very cheerful.”

Georgina Fairholme, 1984

Courtesy Architectural Digest

London-born Georgina Fairholme was a protégé of decorator John Fowler, founder of the esteemed London firm of Colefax & Fowler. After matriculating at London’s St. Martin’s School of Art, she worked at interior designer Joy King’s Elizabeth Eaton shop in Belgravia before joining Colefax & Fowler in 1964. She re-located to New York to work in the firm’s Manhattan office and later joined Rose Cumming, in whose studio she presumably met Cultra.

The Cultra-Fairholme partnership lasted just three years, from 1971 to 1974. In addition to Jenrette, former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis was a client. They worked at her Peapack, New Jersey, equestrian retreat and her Manhattan apartment. The library that the pair decorated in Onassis’s Manhattan residence was photographed by Horst P. Horst and featured in the June 1973 issue of Vogue. Following the dissolution of the partnership, Fairholme remained in New York City, opening her own firm with a client list that included Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon as well as Mr. and Mrs. John Hay “Jock” Whitney. In 1986, Architectural Digest called Fairholme the “doyenne of English Country Style.”

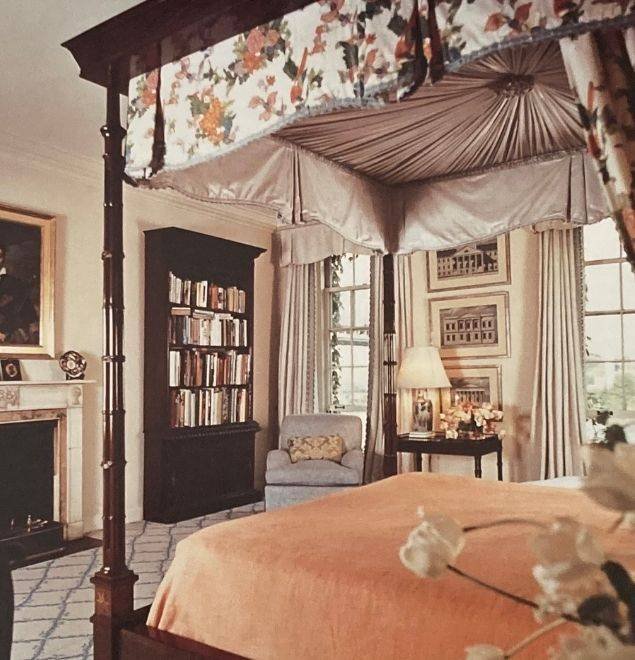

Jenrette's Sutton Place bedroom, c. 1984

Jenrette later called the Cultra-Fairholme collaboration for Sutton Place “a house straight out of the British National Trust,” noting that it was exactly the look he desired. The drawing room was decorated in blue with fabric-covered walls and white silk window treatments framing the tripartite window overlooking the garden and the East River. The first-floor dining room retained the original Vanderbilt-era checkerboard black and white marble floor and a pair of French doors that opened into the garden. Cultra and Fairholme painted the room pumpkin orange with white trim and selected complementary gold window treatments for the double doors and adjacent windows. Jenrette’s third floor bedroom featured English antiques, including a large George III bed with bamboo-turned posts that remains as part of the Jenrette Foundation’s collection. During the 1974 financial crisis, Jenrette made the difficult decision to sell 1 Sutton Place after living in the house for just over a year.

Jenrette's "conversion to Americana" can be attributed to weekends antiquing in Dutchess and Ulster Counties in New York.

It was also in the early-1970s that Jenrette underwent his “conversion to Americana,” as he later called it. The catalyst for this newfound collecting interest on American decorative arts was weekends at Edgewater when he and Bill went antiquing in the surrounding towns and villages of Dutchess and Ulster Counties. It was dealer Fred Johnson who commented that Jenrette owned two of the greatest 19th-century American houses and that he should fill them with American furniture from that same period rather than British antiques of an earlier period. Jenrette heeded the advice and directed his collecting energy toward American decorative arts, focusing on classical New York furniture made between 1800 and 1840.

He later wrote that he was attracted to the furniture of this period by cabinetmakers including Duncan Phyfe, Charles-Honore Lannnuier, Michael Allison, and Joseph Meeks because it represented “an amalgam of English, French, and other European tastes” unlike earlier 18th century American furniture that was largely copied from British examples. To Jenrette, furniture of this period also represented “the final flowering of hand-carved furniture, before machine-made furniture took over as we moved into the Industrial Revolution of the mid-nineteenth century.”

After living in the West 54th Street penthouse apartment for four years, Jenrette purchased a c. 1826 Federal townhouse located at 37 Charlton Street in 1978. In addition to its stunning interior, the house retained virtually all its original architectural details, mantels, and woodwork. Located near Wall Street and Jenrette’s office, it also provided him with an ideal setting in which he could display his growing collection of classical New York furniture. For the renovation of 37 Charlton Street, Jenrette collaborated with Georgia architect Edward Vason Jones (1909-1980). Jenrette first met Jones at a National Trust for Historic Preservation meeting in Charleston. He later said that the architect “helped focus my mind on the fine nuances of American classical architecture as well as his favorite New York Federal-period furnishings.”

Georgia architect Edward Vason Jones

Jenrette Foundation Collection

Jones was a member of what Jenrette called the “Empire Mafia,” a group of collectors and designers with related interests in classical furniture and decorative arts. Other members of the cohort included Berry Tracy, the curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American Wing, and Olympic and World Champion figure skater, Richard “Dick” Button. A self-taught architect, Edward Vason Jones had been hired as a draftsman by the Atlanta firm of Hentz, Adler, and Shutze, and later established his own practice in his hometown of Albany, Georgia. In 1970, Jones collaborated with Berry Tracy on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 19th Century period rooms as part of the museum’s landmark centennial exhibition, “Nineteenth Century America.” Jones subsequently assisted with the restoration of the public rooms of The White House during the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations. He also worked with Clement Conger on the creation of the Diplomatic Reception Rooms, a project that transformed two floors of the State Department’ bland mid-20th century Washington, D.C. office building into a venue where the Secretary of State could receive diplomats, dignitaries, and foreign heads of state in grand spaces furnished with 18th and 19th century American decorative arts and fine art.

Edward Vason Jones designed the carpet used for the Charlton Street double parlor, copying a motif from an early 19th century Aubusson carpet Jenrette owned that was too fragile to use. Window treatments were created by one of Jones’ frequent collaborators, designer David Richmond Byers III (1921-1998). Byers was an Atlanta decorator who had worked with Jones on both Washington, D.C., projects. Born in Baltimore, Byers had studied architecture at the University of Virginia and began his career at the Atlanta firm W.E. Browne Decorating Company in 1945. After starting his own design business, his projects included decorating the Georgia Governor’s Mansion as well as future projects for Jenrette at Edgewater, Roper House, and Ayr Mount.

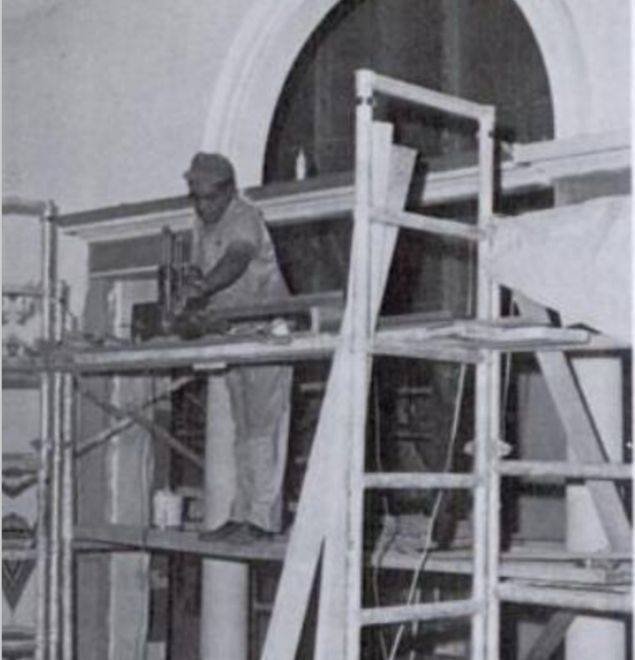

Odolph Blaylock at work on State Department’s Diplomatic Reception Rooms, 1974

Jenrette Foundation Collection

For the Charlton Street restoration, Jones utilized the small team of master craftsman who were his frequent collaborators because he considered them to be the best practitioners of their respective trades. Odolph Blaylock (1915-2005) of Albany, Georgia served as foreman and head carpenter, a position he also held on other Jones projects including the Diplomatic Reception Rooms. A self-taught craftsman who grew up in Jim Crow-era Georgia, Blaylock began working for Jones in 1949. At Charlton Street, he ran the plaster molding and installed plaster ornaments designed by Jones. In 1985, Blaylock received The Institute for Classical Architecture and Art’s Arthur Ross Award in the field of artisanship. Other craftsmen from Jones’s team included carver Herbert Millard and plasterer David Flaharty. In describing the restoration of 37 Charlton Street in the February 1982 issue of The Connoisseur, Charles Lockwood wrote that “Jenrette’s townhouse still evokes a feeling of a comfortable private home, not a series of showcase museum rooms.” In a 1982 New York Times article, reporter John Duke praised the project and said that it represented “a high-water mark in meticulous private restoration.” Duke also described the restored double parlor at 37 Charlton Street as “a comforting blend of warmth and history.”

Following his conversion to Americana, Jenrette redecorated and refurnished Edgewater in a manner that better reflected its previous appearance under its19th-century owners, Mr. and Mrs. Lowndes Brown and Mr. and Mrs. Robert Donaldson. Walls were repainted, and antique European carpets were removed in favor of new wall-to-wall carpeting in classical motifs. Using historic documents, including Robert Donaldson’s 1872 estate inventory, Jenrette and Thompson began to furnish the house with New York furniture with regional histories. After learning that Donaldson had displayed a set of Hudson River Portfolio aquatints at Edgewater, they assembled the full series of twenty images depicting scenes along the Hudson River printed between 1821 and 1825.

In 1973, Harrison Cultra alerted Jenrette to a Magazine Antiques article on artist George Cooke featuring his 1832 portrait of Robert Donaldson’s wife, Susan, in the Brooklyn Museum collection. When Jenrette visited the Brooklyn Museum to see the portrait that had previously hung at Edgewater, he discovered that three original pieces of Donaldson furniture commissioned from New York cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe in the 1820s, were also in the collection. Eager but unable to acquire these objects from the Brooklyn Museum, Jenrette was allowed to have them on long-term loan and display them at Edgewater, returning important original objects to the house.

Canterbury, a type of stand historically used to hold sheet music, tableware, and, later, magazines; attributed to Duncan Phyfe, Jenrette Foundation Collection #2018.018

Through the assistance of longtime friend and UNC classmate Dr. John Saunders, Jenrette was introduced to Donaldson’s last living descendant, Mary Stuart Cromwell Allison, a great-granddaughter who lived on the Mediterranean coast of Spain. Jenrette was able to visit Mrs. Allison and see the collection of Donaldson family portraits, furniture, silver, documents, and other objects displayed in her home that were formerly used at Edgewater. As she had no heirs and was impressed with Jenrette’s passion for restoring her family’s ancestral property, Mrs. Allison bequeathed the collection to him. Upon her death in 1976, these important objects returned to Edgewater nearly 100 years after they had left. The Magazine Antiques featured Edgewater on the cover of its June 1982 issue with images of the interior spaces re-furnished with Jenrette’s growing collection of American decorative arts, including many of those original Donaldson objects that he received from Mrs. Allison.

Edgewater's Octagonal Library, designed by A.J. Davis and added by Robert Donaldson in the 1850s.

In 2010, designer Thomas Jayne included Edgewater’s Octagon Library, in his book, The Finest Rooms in America. Jayne wrote that the architecture of the space was “enhanced with the historically informed decoration of Bill Thompson.” Thompson’s design for the “grandly scaled classical carpet,” manufactured by Scalamandre for that space, was patterned on the ceiling of a Roman building in Pompeii.

Dick Jenrette in Edgewater Library, 1980. Jenrette Foundation Collection

As Jayne noted, “the genius of the design lies in the juxtaposition of large geometric shapes, repeated by the center table and even the globes, with the polygonal plan of the room.”

The walls of the Octagon Library were faux marbled to resemble ashlar blocks and hung with paintings from Jenrette’s collection. The frieze, surmounting the 21-foot-high walls, is, as Jayne notes, “embellished with a green and gilt border of acanthus leaves, which echo the color of the carpet” and draws the eye upward towards the oculus skylight at the center of the room. After Mrs. Hastie died in 1981, Jenrette undertook a two-year restoration of Roper House. He now focused on the first and second floor spaces, removing walls that were added in the 20th century and unifying the two second floor spaces that originally served as the Double Parlor. As Edward Vason Jones had passed away in 1980, David Richmond Byers III served as principle designer for this project.

In their 1990 Magazine Antiques article on Roper House, Kenneth and Martha Severens called Roper’s impressive Double Parlor the “climax of the formal sequence of rooms” and described how the walls had been “marbleized in illusionistic panels” during Jenrette’s renovation. In addition to the faux marbling, the wooden floors were embellished with stenciling and painted marquetry patterns. Window treatments of blue silk with elaborate gold fringe designed by Byers framed the eleven-foot-tall triple-hung windows of the Double Parlor that provide sweeping views of Charleston’s harbor. The carpet was designed by Bill Thompson and copied from one in the Senate chamber of the Old State Capitol Building in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Second-floor front parlor of Roper House, 9 East Battery, Charleston, South Carolina, 1838.

The Double Parlor at Roper House became another ideal setting for Jenrette to display notable pieces of Duncan Phyfe furniture, including a secretary bookcase, a late Federal/Early Empire transitional Grecian sofa, a fall-front desk, and a suite of curule-form side-chairs. The sofa, chairs, and other pieces of seating furniture throughout the space were all upholstered en suite with Scalamandre’s “Monroe Bee” silk lampas in royal blue and gold. Over the pair of Egyptian marble mantels, Jenrette hung a “porthole” portrait of George Washington by Harriet Cany Peale, copied from her husband Rembrandt Peale’s iconic likeness, and another of General William Moultrie of Charleston, attributed to artist Mather Brown.

Ayr Mount, Hillsborough, North Carolina, purchased and restored by Jenrette in 1985. Jenrette Foundation Collection

The dining room at Ayr Mount, decorated by David Richmond Byers III; photograph by Bruce Schwarz, Jenrette Foundation Collection

In 1985, Jenrette purchased Ayr Mount in Hillsborough, North Carolina. The c. 1815 house was the earliest brick dwelling in Orange County, North Carolina, and it had been under the continual ownership of the Kirkland family since its construction for patriarch William Kirkland. Todd Dickinson, a North Carolina-based contractor, oversaw a systematic two-year restoration of the house. Paint analysis by George Fore revealed original paint colors, which were reproduced. After the completion of the restoration, David Richmond Byers III decorated the house. Byers supplemented original Kirkland furniture and objects with contemporary examples of New York furniture from Jenrette’s collection and for the windows, he created “simple yet elegant hangings, suitable for a house of this period and quality.”

The George F. Baker House, designed by Delano & Aldrich and completed in 1930, was Jenrette's New York City home, 1987-89 and 1996-2018.

In 1987, Jenrette purchased the 1930 Delano & Aldrich designed George F. Baker house in Manhattan’s Carnegie Hill neighborhood so he could live in closer proximity to his offices at the Equitable’s headquarters. He owned the townhouse for only two years before selling it and purchasing its next-door neighbor, 69 East 93rd. Also designed by Delano & Aldrich and built in 1929, the adjoining house had originally served as a garage and servant quarters for Baker’s Park Avenue mansion that was located across the courtyard. In the 1940s, George F. Baker Jr.’s widow, Edith Brevoort Kane Baker, had number 69 renovated and transformed the upper floors into a pied-a-terre for her use in the city since her primary residence was a Long Island estate. The carriage house was still owned by the Baker Family in 1989 when they sold it to Jenrette.

Jenrette and Thompson lived in number 69 for seven years. The living spaces, atop a spacious garage that could hold five automobiles, were located on the third and fourth floors. Its most impressive feature was the monumental portico on the east façade with massive Ionic columns and huge windows that flooded the house with light. Jenrette considered it to be, “one of the most handsome facades in Manhattan.” The Drawing Room, with paired floor-to-ceiling bookcases flanking the fireplace, was furnished with Phyfe furniture as well as modern upholstered seating furniture. Jenrette added an early-19th century Adam-style mantel by Philadelphia carver and composition ornament maker Robert Wellford to serve as the focal point of the room. His fourth-floor master bedroom featured a delft-tiled fireplace surround flanked by built-in bookcases, comfortable seating furniture, and a Caribbean mahogany bed.

The sitting Room of 69 E. 93rd Street, designed by John Hall, which featured an early-19th century Adam-style mantel by Philadelphia carver and composition ornament maker Robert Wellford.

When an opportunity arose in 1996, Jenrette re-purchased #67 at a substantially lower price than what he had sold it for seven years earlier. This time, no designers were brought in. Jenrette did the work himself with Thompson’s assistance, describing the project during an interview with Architectural Digest in 2000, stating “I’ve worked closely with so many designers over the years, and I know where to find wonderful artisans— painters, gilders, drapery designers—which is half the battle. The idea of doing it myself just sort of evolved.”

As he wrote in Adventures With Old Houses, “having had the equivalent of a post-graduate degree from working with so many great interior designers over the years, I decided to forego an outside decorator.” One design choice was the selection of a rich chocolate brown for the oval dining room located at the rear of the house. The color complemented the beige and brown marble tiled floor and made the white marble mantel, pilasters, and the collection of white statuary marble busts a focal point within the space. Bill Thompson designed a set of yellow and white silk curtains with swags for the bowed windows along the back wall. In the stair hall of #67, Jenrette installed a Georgian-style glass lantern from 1 Sutton Place, an object he had retained since moving out of that house more twenty-years earlier.

The third floor drawing room at number 67 was painted a vibrant blue—a color Jenrette had seen in a book about Marie Antoinette’s apartments at Versailles. After noticing that his favorite mahogany furniture disappeared against the dark colored walls, he furnished the space with Continental European furniture in lighter colored woods, including a pair of large satinwood Charles X bookcases by French cabinetmaker Georges-Alphonce Jacob Desmalter (1799-1870), the third-generation cabinetmaker of the notable Parisian family.

Jenrette's use of blue in the drawing room at number 67 was inspired by Marie Antoinette’s apartments at Versailles.

Jenrette’s Master Bedroom incorporated his favorite “Carolina blue” bed hangings on a Duncan Phyfe tall-post bed and another Bill Thompson-designed carpet. The fourth floor Guest Bedroom featured peach-colored walls and yellow bed hangings and window treatments that were “inspired by Nancy Lancaster’s decorating in England,” Jenrette noted. After completing the project, he wrote that “doing the decorating myself this time also may have been more satisfying” and that he found Baker House his “favorite residence of the many residences I have had in New York.”

Dick Jenrette at Millford, 1982. Jenrette Foundation Collection

Jenrette purchased his final historic property, Millford, in 1992. The three-hundred-acre Sumter County, South Carolina house, built in the 1840s by John Laurence Manning and his wife Susan Hampton Manning boasted a mansion that is considered to be the preeminent example of Greek Revival residential architecture in the United States.

Millford retained nearly all its original interior details, including window and door architraves that were directly copied from plates in Minard LaFever’s Beauties of Modern Architecture (1835). Original marble mantels from Philadelphia, silvered door hardware from New York City, and lighting sourced from a Charleston silversmith at the time of Millford’s construction remained in the house. Several pieces of original furniture commissioned by the Mannings from Duncan Phyfe & Son of New York had also remained in the house, and additional pieces were found in storage in the attic.

The double parlor at Millford is a highlight for a property that retained nearly all its original interior details, including window and door architraves directly copied from plates in Minard LaFever’s Beauties of Modern Architecture.

Millford was built between 1840 and 1842 by Nathaniel Potter in Sumter County, South Carolina.

Jenrette undertook his own restoration of Millford’s mansion and some of the adjacent outbuildings. He decorated the house with pieces of the original Phyfe & Son furniture that were supplemented with other objects from his collection. The mansion’s walls were faux marbled, and floors were stenciled in a tromp l’oeil motif by Robert Jackson. Bill Thompson designed carpets featuring classical motifs as well as window treatments and bed hangings.

Jenrette and Thompson also sought and acquired additional examples of original Millford furniture, Manning and Richardson family portraits, silver, ephemera, and other objects that were dispersed following the 1902 sale of the property by the heirs of John Laurence Manning. Millford was, as Jenrette recalled, “my dream house with big columns on the hill, down south, overlooking acres of green lawn and moss-draped live oak trees.”

The interiors of Jenrette’s houses described in this article were frequently featured on the pages of The Magazine Antiques, Town & Country, Architectural Digest, The Connoisseur, and The New York Times. As Jenrette’s taste and collecting focus matured, the décor and furnishing of his houses also evolved from his European phase through his conversion to Americana in the mid-1970s, and finally to the period where he and Thompson undertook the decoration of the interiors themselves. “I believe I have had a role in creating beauty,” Jenrette wrote, “at least in restoring these beautiful old houses and antiques to their former glory and preserving them as models for future generations to enjoy.”