The Great Trading Path

Author: Kevin Cherry, PhD

Ayr Mount was built in 1815 for the Kirkland family

In the strip of woods facing the front of Ayr Mount is a depressed spot covered in leaves and small plants and sporting a few trees here and there. To the casual glance, this piece of ground is nothing more than a shallow wash or gully, but a closer look reveals evidence of one of Ayr Mount’s most important landscape features: the remnants of a prehistoric path and later colonial road.

The Great Trading Path, sometimes called the Occaneechi Path, was one of two major Indian trading paths that passed through what would become North Carolina, the other being the Warrior’s Path, later called the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road. The local Siouan tribes, Saponi and Occeeneechee, among others, often acted as the middlemen in the commerce along this path, trading with the Cherokee and Catawba (who were each other’s traditional enemies) and then with the Europeans.

Long before Europeans came to this part of the world, American Indians traded goods between themselves and other tribes, regularly traveling between settlements.

An untouched portion of the Great Trading Path situated at the front of Ayr Mount's property, October 2020.

Jenrette Foundation Collection

In the earliest days, they probably followed paths made by animals, and over time these paths grew and became easier to navigate. Out of the multitude of paths, large and small, that must’ve once crisscrossed what we now call North Carolina, the remnants of eighteen have been identified, and none are more important than the stretch of ground near Ayr Mount, which marks the location of the Great Trading Path.

With Europeans arrival in the 1670s came an increased demand for furs, and the booming fur trade led the path to evolve, moving from sliver in the middle of the woods to something more substantial, eventually becoming a wagon road beginning in 1740s.

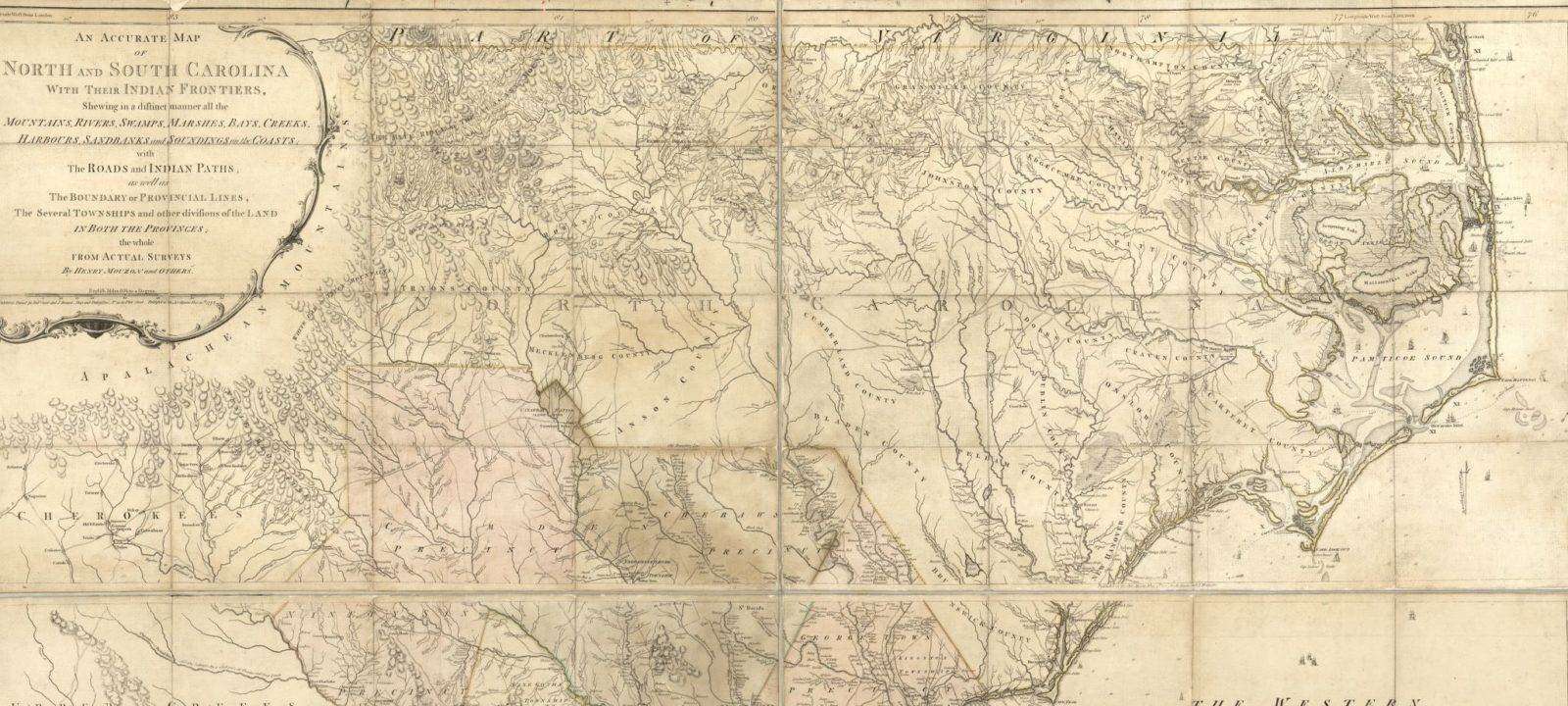

In 1775, Henry Mouzon, Jr. (1741-1807) created "An Accurate Map of North and South Carolina with their Indian Frontiers, Shewing in a distinct manner all the Mountains, Rivers, Swamps, Marshes, Bays, Creeks, Harbours, Sandbanks and Soundings on the Coasts; with The Roads and Indian Paths; as well as The Boundary or Provincial Lines, The Several Townships and other divisions of the Land In Both the Provinces," which offers clues about the relationship between regional trading paths and settlement patterns.

Pelts, metal tools, cloths, blankets, ammunition, firearms, and decorative items, piled on the back of pack animals, traveled the Great Trading Path, which originated near Fort Henry, now Petersburg, Virginia, and traveled to Occaneechi Island, now Clarksville, Virginia. From there it headed south to cross the Tar River near Oxford, and from there it ran southwest, crossing the Eno in Hillsborough, the Haw near Swepsonville, the Uwharrie near Asheboro, and the Yadkin at Trading Ford, near Spencer. (I85 crossing the Yadkin close to this ford.) The path then headed south toward Charlotte and the Catawba nation near Waxhaw. It then split with one branch headed toward Columbia, SC and the other toward the Cherokee settlements around Augusta, Georgia.

A well-travelled, thin line through the forests.

The Summer Brothers and Pomaria n his search for the Pacific, thought to be just over the mountains in western Virginia, the German physician and explorer Johan Lederer stumbled upon the Great Trading Path. He became perhaps the first European to describe it in writing in 1670.

Three years later, James Needham and Gabriel Arthur also recorded their use of the path.

In 1701, John Lawson recorded what would probably be the most cited of all of these sources. These descriptions picture a well-travelled, thin line through the forests.

This thin line may be found on the Moseley Map of 1733, the Collett Map of 1770, and the Mouzon map of 1775, all noted early maps of the region.

Kirkland likely took cues about Ayr Mount's siting and orientation from the Great Trading Path.

The location of the Great Trading Path probably helped dictate the location and orientation of Ayr Mount.

By the time William Kirkland started building his large brick home, the Great Trading Path was a major commercial road, bringing goods on wagons along the same trade route those pelts of 100 years earlier had traveled.

It was only appropriate that Kirkland, a merchant through-and-through, would place his home alongside this important business thoroughfare.

A great deal of commerce made its way along this path over the years, and in its present form, now largely Interstate 85 running from Durham, North Carolina through Charlotte, North Carolina, it still plays this important role.