The Historic Houses of Richard H. Jenrette, Part I: The Houses

Author: Grant Quertermous

Learn more about the Jenrette Foundation’s properties

“There’s no place like home,” Richard H. Jenrette wrote in his book, Adventures With Old Houses, “the older the better.” During his lifetime, Jenrette owned and restored fourteen homes, including the ones that remain in the care of the Jenrette Foundation.

A self-proclaimed “house-aholic,” the list included a succession of New York City houses that he used as his primary city residence while working as a founding partner of the Wall Street investment bank Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette (DLJ) and later as Chairman and C.E.O. of The Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States until his 1996 retirement.

In addition to undertaking the restoration of these properties, Jenrette served as one of three partners on a project in the late 1960s that reconstructed the historic Mills House Hotel in Charleston, and he was appointed by President Jimmy Carter as Chair of the President’s Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

Sutton Place, New York

Jenrette’s first New York City residence was a one-bedroom co-op apartment located at 455 East 57th Street. The maisonette was, as Jenrette recalled, “the first piece of real estate I ever owned.” Located near the corner of 57thStreet and Sutton Place, the sixteen-story pre-war building was constructed in 1928. After seeing the apartment, a colleague of Jenrette’s at DLJ encouraged him to hire North Carolina-based designer Otto Zenke (1904-1984) as a decorator. (Zenke’s work is discussed in Part II of this series that focuses on the décor and furnishing of each of the houses.)

For a period of two years in the mid-1960s, Jenrette lived abroad in Europe where he worked to establish a Continental presence for Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. He rented an 18th century farmhouse outside Brussels, Belgium, near the site where the Battle of Waterloo occurred in 1815. Designer Otto Zenke, working out of his London studio, also decorated this house for Jenrette.

Roper House, Charleston

Jenrette beneath Roper House's towering columns on the side porch "piazza."

It was during a moonlit stroll with friends along Charleston’s High Battery in 1968 that Jenrette first saw Roper House with its monumental piazza and towering columns. He purchased the house in 1968, owning it for the next fifty years until his 2018 death.

As part of the purchase agreement, Jenrette initially resided on the third floor while the second floor was occupied by the previous owner’s widowed mother for a period of twelve years. When asked how he first discovered Charleston in a 2005 interview, Jenrette responded that he had taken a weekend trip to Hilton Head Island in the mid-1960s, and it rained nonstop, so he drove up to Charleston and was captivated by the city.

He also purchased and restored the William Blacklock House, a ca. 1800 house on Charleston’s Bull Street as well as several adjacent houses, all of which he donated to The College of Charleston in the 1970s. However, Roper wasn’t his first purchase of Charleston real estate. He first purchased a house on Anderson Street but sold it before undertaking renovations after learning it would cost more than seven times its purchase price to complete a renovation.

E. 11th Street, New York

In 1969, Jenrette purchased a ca. 1840 Greek Revival townhouse at 27 E. 11th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village. The house had fourteen-foot ceilings, large windows, and original wrought-iron grillwork railings on the exterior. Jenrette occupied the first floor while the upper floors of the house contained two rent-controlled apartments. The tenants included a Broadway dancer who tap-danced loudly on the floor just above Jenrette’s bedroom into the early morning hours. Not able to evict the tenants through an appeal to the New York City Rent Control Board, he sold the property in August 1970 and moved further uptown. “It was just too large and I decided I would just prefer not to be a landlord in Manhattan,” he told The New York Times in 1971, “I also don’t like people trooping over my head.”

An Edward F. Knowles-designed home, in section, whose plans were later abandoned by Jenrette

Desirous of a weekend home that was in closer proximity to New York City than Roper House, Jenrette commissioned the well-known modernist architect Edward F. Knowles (1929-2018) to design a weekend home for a hillside parcel of property in New Jersey overlooking the Delaware River. Knowles is best-known for designing Boston’s brutalist City Hall and The Filene Center at Virginia’s Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts. Jenrette later described the planned house as “a series of three high-ceilinged cubes: mostly glass with connecting terraces with a ‘drop-dead view’ down the river to the distant Delaware Water Gap.” Before construction could begin, Jenrette discovered and purchased Edgewater, which he said made him “suddenly forget the glass house I proposed to build in New Jersey.” He later sold the New Jersey property in the fall of 1970.

Edgewater, Barrytown

It was during a Saturday drive in late September 1969 that Jenrette and his partner William L. Thompson found Edgewater, seeking out the property after seeing an image of the house in their copy of Eberline and Hubbard’s Historic Houses of the Hudson Valley. Located about 100 miles north of New York City, Edgewater is situated on a small peninsula surrounded by lagoons of the Hudson River and a shoreline of weeping willow and beech trees. The ca. 1824 house is atypical of Hudson River Valley regional architecture, but its original owner Rawlins Lowndes Brown was a South Carolinian from Charleston who had married into the Livingston family of Dutchess County, New York.

Jenrette paddling near Edgewater's shore, c. 1975

Its location was ideally suited for use as a weekend home and a place to escape the traffic and noise of Manhattan. At the time, Edgewater was owned by author Gore Vidal, who was living abroad in Italy. Coincidentally, the day after his drive to find Edgewater, Jenrette learned from designer Anthony Hail, who had just returned from Italy, that the author was planning to sell the house. “It’s to die for — you ought to buy it!” Jenrette later recalled the designer telling him. Three days later, Jenrette concluded a Trans-Atlantic negotiation with Vidal and purchased the property. As he later described, the closing took place over a drink at Vidal’s New York apartment. Actress Shirley MacLaine, who Jenrette had recently seen perform on Broadway in Sweet Charity, answered the door and handed him a cocktail and the telephone so he could speak to Vidal who was in Rome. Jenrette called Edgewater, “the love of my life, architecturally speaking” and used the property as a riverside retreat for the rest of his life.

E. 38th Street, New York

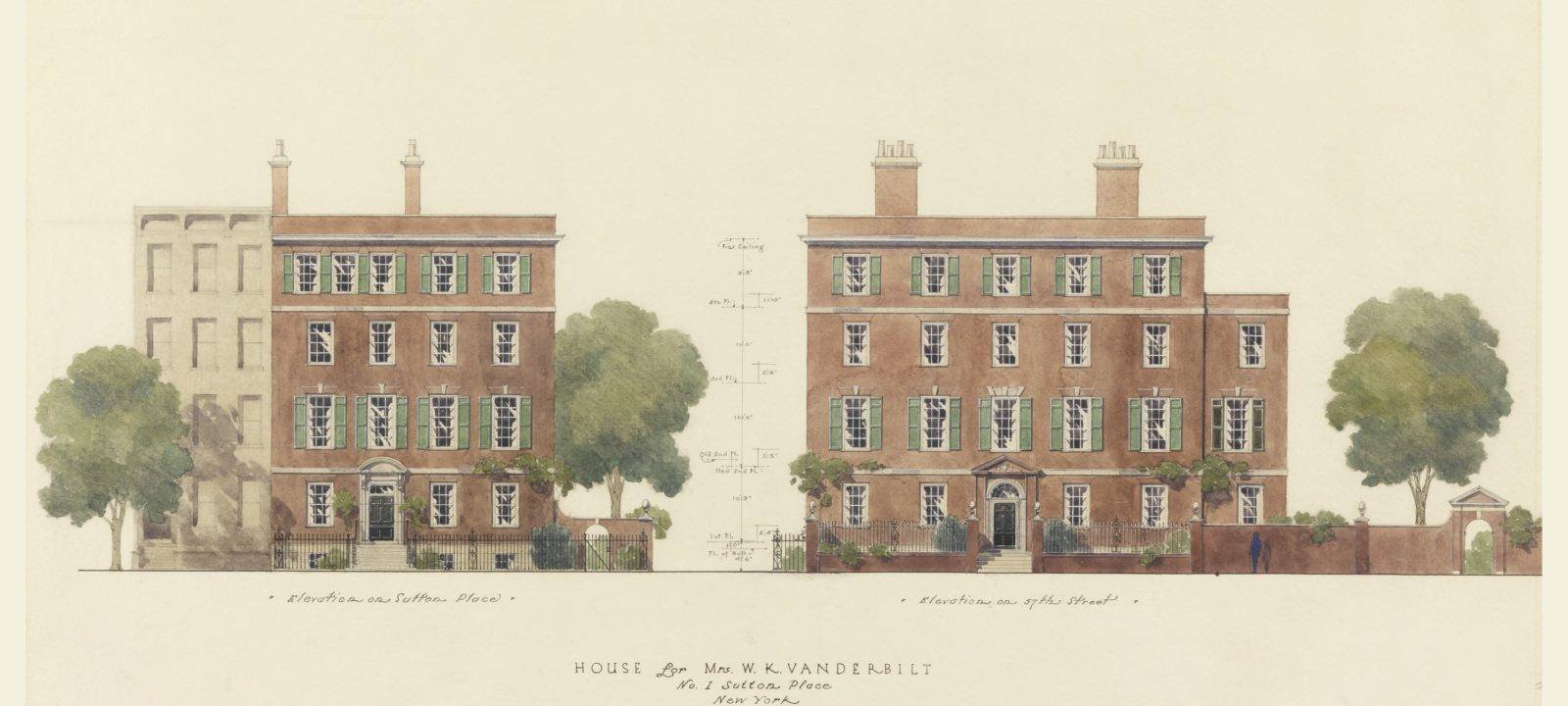

In March of 1970, Jenrette purchased a ca. 1858 house located at 150 E. 38th Street in the Murray Hill neighborhood of Manhattan from publisher Cass Canfield, the longtime president and chairman of Harper & Brothers. The house was unique as it was placed several yards back from the sidewalk providing space for a small garden courtyard. A loggia supported by columns and wrought-iron grillwork led from the street to an inner courtyard garden. In 1934, tenant Russell Pettengill commissioned architect Robertson Ward to convert the house and an adjacent dwelling into his residence and office. At the time the front garden was divided by the construction of a red brick wall with a pair of arched entrance gates. Pettengill left in 1935 when Cass Canfield purchased the property, living there until its 1970 sale to Jenrette. The three-story house had double parlors on the first floor with bedchambers located on the second and third floors and a room across the full width of the house on the second floor that Jenrette used as an office and library. He described this house as “the perfect pied-a-terre,” noting its location on East 38th street as convenient to both uptown and downtown Manhattan. After residing on East 38th street for less than two years, Jenrette purchased 1 Sutton Place in 1972, the house that he later described as the one that “got away.” Jenrette was familiar with the house from his days living in an apartment on East 57th street, just half a block away from Sutton Place. He and Thompson had first visited the house in December of 1971, and he described it in his diary as “a jewel of a house” and noted that he would “love to own [it]—just [the] right size.” The neo-Georgian townhouse designed by architect Mott Schmidt (1889-1977) was located at the northeast corner of Sutton Place and 57th Street. Completed in 1921, the house was built for Anne Harriman Vanderbilt, widow of William K. Vanderbilt, and it was later owned by Charles Merrill, the co-founder of Merrill Lynch.

Mott Schmidt designed adjoining neo-Georgian townhouses on Sutton Place and 57th Street, New York

The adjoining townhouse, also designed by Schmidt, was built for Anne Tracey Morgan, the daughter of financier J.P. Morgan, and is now home to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. The house and other adjacent townhouses on the square enclosed a common garden built out over East River Drive and overlooked Sutton Park with scenic views of the East River and the Queensboro Bridge. In the midst of the 1974 financial crisis, Jenrette, who by this time owned three houses: Roper House, Edgewater and 1 Sutton Place, made the difficult decision to sell the New York townhouse, which he called “the finest town house in Manhattan” after living in it for just over one year. The buyer was Mr. and Mrs. Henry John Heinz II. Mr. Heinz died in 1987, but Mrs. Heinz lived at 1 Sutton Place from the time of their 1974 purchase until her 2018 death.

Jenrette’s penthouse was located at W. 54th Street, New York, designed by architects Wallace K. Harrison and Jacques André Fouilhoux

After selling 1 Sutton Place, Jenrette purchased a two-bedroom penthouse apartment located on the top floor of The Rockefeller Apartments, a ca. 1936 art-deco building located at 17 W. 54th Street. The building and a matching tower on W. 55th Street were designed by architects Wallace Harrison and Jacques André Fouilhoux, both of whom were also involved in the design of Rockefeller Center. The apartment building was constructed on land that was owned by the Rockefeller family. The balcony patio of Jenrette’s penthouse offered a birds-eye view into the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden at the adjacent Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) and “a spectacular in-your-face view of the Manhattan skyline.” While he later recalled that he enjoyed the building’s close proximity to many of midtown Manhattan’s best restaurants, Jenrette wrote that he disliked apartment living because it forced him to spend so much time waiting for elevators.

37 Charlton Street, New York

After living in the penthouse apartment for four years, he purchased a Federal townhouse located at 37 Charlton Street in 1978. “The house seemed perfect,” Jenrette recalled, “it had been virtually untouched in its 150-year history, but structurally was still sound.” The original architectural details throughout the house provided an ideal venue for his growing collection of Classical New York furniture by cabinetmakers such as Duncan Phyfe, and it was located in close proximity to Wall Street.

The 1827 townhouse had a storied history. Developed by fur-trader John Jacob Astor, the block of townhouses on Charlton Street was built on what was originally the location of Richmond Hill, a mansion used by General George Washington during the American Revolution, subsequently owned by Aaron Burr, and later inhabited by Vice President John Adams as his official residence when New York City served as the nation’s capital. The federal townhouse, known as the John V. Gridley House, was one of several completed in 1827 after the block was sub-divided into lots for sale. Nearly destroyed by fire, the house was reconstructed in 1829. In the late 19th century, the house had served as the headquarters of the Third Assembly District Tammany Club. It was given a third story in 1917 as part of a renovation, but it retained all of the original black marble mantels, decorative molding, doors, and window architraves on the lower floors. The entrance of 37 Charlton Street is one especially notable feature of the house with fluted columns flanking the original door, leaded glass sidelights, quarter-columns, and a white stone entablature.

In an 1899 Architectural Record article, critic Montgomery Schuyler lamented the already rapidly disappearing Federal houses in the city, commenting that among the “best examples” surviving from that time period were “two rows, one in Vandam Street and one in Charlton” which included No. 37. In 1966, The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission called No. 37 Charlton Street and its contemporaneous twin at No. 39, “perhaps the two most important houses in age, richness of style, scale, and perfection of preservation” among those being proposed for inclusion in the Charlton-King-Vandam Historic District. After nine years, Jenrette sold the Charlton Street townhouse in 1987 in order to move further uptown. From 2004 until 2015, it served as a rectory for Manhattan’s Trinity Church, but is now once again a private home.

Ayr Mount, Hillsborough

In 1985, Jenrette purchased Ayr Mount in Hillsborough, North Carolina. The ca. 1815 house was the earliest brick dwelling in Orange County, North Carolina, and had been continuously owned by the descendants of its original owner, William Kirkland, since its construction. At the time Jenrette purchased Ayr Mount, he was mulling a retirement that included teaching at a university, and Ayr Mount’s location in Hillsborough was almost equidistant between Duke University in Durham and the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Any thoughts of retirement were postponed when Jenrette was asked to become Chairman of the Board of The Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States. Nevertheless, Ayr Mount was the first property that he gave to Classical American Homes Preservation Trust after he undertook a serious-two-year restoration that included paint analysis to determine the appropriate colors for walls, woodwork, and baseboards throughout the house.

Cane Garden, St. Croix

That same year, Jenrette also purchased Cane Garden, an 18th century Danish sugar plantation on the island of St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, a property that he intended to use as a winter retreat. He had rented the plantation for a week the previous winter, and following the death of its owner, Jenrette was approached by the estate’s executors who asked if he had any interest in buying the property. The plantation retained its 18th century great house that was located on a high hill overlooking the Caribbean. Renovated in the neoclassical style around 1820, a portion of the house had been further reconstructed in the early 20th century following a fire. The plantation also retained many of its original 18th and 19th century dependencies and a mile-long stretch of private white-sand beach. Jenrette retained Cane Garden for the rest of his life, and, in accordance with his wishes, Classical American Homes Preservation Trust sold the property in the summer of 2020.

Baker House, 67 E. 93rd Street, New York, designed by Delano & Aldrich

In 1987, Jenrette moved further uptown in Manhattan and purchased Baker House, a 1931 Delano & Aldrich-designed townhouse located at 67 E. 93rd Street, an address that was more convenient to his office at The Equitable than the Charlton Street house. The townhouse was originally constructed for George F. Baker Sr. and was part of a larger complex of buildings, all designed by Delano & Aldrich, that included a large mansion at the corner of Park Avenue and East 93rd that was the residence of Baker’s son, financier George F. Baker Jr. The townhouse at #67 had been constructed by George F. Baker Jr. for his aged father, but the elder Baker died before he could occupy the house. Jenrette described George F. Baker Sr. as one of his “larger-than-life heroes in business history” due to the financier’s role in endowing the Harvard University Graduate School of Business, so he felt an immediate connection to the house. Jenrette owned the townhouse for only two years before selling it to an art dealer for a substantial profit and purchasing its next-door neighbor at 69 E. 93rd. Also designed by Delano & Aldrich and built in 1929, this carriage house originally served as a garage and servant quarters for the younger Baker’s Park Avenue mansion that was located across an open courtyard. In the 1940s, George F. Baker Jr’s widow Edith Brevoort Kane Baker had renovated the building and transformed the upper floors into a pied-a-terre as her primary residence was an estate on Long Island. The carriage house was still owned by the Baker family when they sold it to Mr. Jenrette in 1989.

67 E. 93rd Street, New York

Jenrette lived in #69 for seven years, and, when the opportunity arose, he re-purchased the adjacent townhouse at #67 in 1996, at a substantially lower price that what he had sold it for in 1989. Jenrette retained both properties, later giving #69 to the Classical American Homes Preservation Trust (later the Jenrette Foundation) to use as its administrative headquarters, a role it served until the organization’s headquarters officially moved to Ayr Mount in Hillsborough, North Carolina in 2021. The townhouse at 67 E. 93rd remained Richard H. Jenrette’s Manhattan residence until his 2018 death.

Millford, Sumter County, South Carolina

Jenrette’s final historic property, Millford, located in Sumter County, South Carolina, was purchased in 1992. He later wrote that buying Millford, “arguably the finest extant example of Greek Revival residential architecture in America,” was his “reward” for rescuing The Equitable and making it into a profitable company. Constructed by John Laurence Manning, the future Governor of South Carolina, and his wife Susan Hampton Manning, Millford was a showplace of Manning’s wealth, which he had made in the sale of sugar from plantations he owned in Louisiana. Its remote location helped to preserve not only its main house, but numerous original outbuildings on the three-hundred-acre tract Jenrette acquired. When he purchased Millford, Jenrette also received numerous pieces of furniture by New York cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe that were original to the house, commissioned by John Laurence Manning between 1839 and 1842. The furniture had remained with the house through its subsequent owners. Jenrette and Thompson sought out and acquired additional pieces of Millford furniture, Manning family portraits, and other objects associated with the house. Jenrette also restored original outbuildings, updated the landscaping around the mansion, and added a swimming pool.

Jenrette and his partner, William L. “Bill” Thompson at Millford

After his retirement from the Equitable, Jenrette devoted much of his time to nurturing the Classical American Homes Preservation Trust. He and his partner, William L. Thompson, traveled frequently and spent a portion of every year at each of the properties. They typically spent late summer and fall at Edgewater in the Hudson River Valley, winters in the Caribbean at Cane Garden, and spring and early summer in South Carolina at both Roper House and Millford. It was the 1968 purchase of Roper House that first awakened Jenrette’s interest in historic preservation. He later wrote, “my love affair with Roper House was just the beginning of what has turned out to be a fascinating lifetime career of restoring classical American homes.” He also credited his ownership of Roper House with enhancing his “appreciation of the value and importance of historic preservation” which led him to create Classical American Homes Preservation Trust in 1993, later renamed the Richard Hampton Jenrette Foundation.