Searching for hidden things Ayr Mount

Author: Joseph Beatty, PhD

Ayr Mount is unlike any other house of its era

On the week of July 24, 2023, the Richard Hampton Jenrette Foundation (then the Classical American Homes Preservation Trust) hosted two days of archaeological investigations at Ayr Mount. Faculty and graduate students from Clemson University and the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill conducted ground penetrating radar (GPR) surveys of two locations to learn more about features that are hidden beneath the surface. GPR is useful, because it allows archaeologists to carry out non-destructive investigations of a site. Without tools like this, we would need to remove significant amounts of soil to look for things that may (or may not) be present, a process that can be both time consuming and irreversible.

Dr. Jon Marcoux from the Clemson University Graduate Program in Historic Preservation led GPR examination of the Ayr Mount cemetery. The stone wall and iron fence around the cemetery are in need of repair, so the goal of this work was to see if there were any unmarked graves or features that might be impacted. Historical records suggest the likelihood of at least two burials for which we do not find headstones.

GPR is useful, because it allows archaeologists to carry out non-destructive investigations of a site (including Ayr Mount).

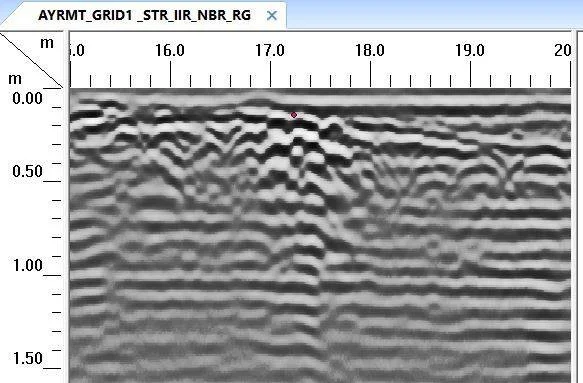

With this in mind, Dr. Marcoux and his students surveyed a perimeter starting six feet outside the walls and everything within. Preliminary results appear to confirm that there are a few unmarked burials inside the walls and none outside. They also identified areas of fill dirt along the north wall and noted what is likely some paving stones near the gate. This is encouraging data, as it gives us the information we need to proceed safely and respectfully with the stabilization and repair of the wall and fence. On the south side of the house, Dr. Mary Beth Fitts from UNC Research Laboratories of Archaeology directed a group of graduate students in search of Ayr Mount’s original support buildings. Historical records suggest that a kitchen, well, icehouse, and shed were located just to the southeast of the home. The team used GPR to survey an 11,000 square-foot area where there was a high likelihood the buildings were located. Preliminary results from this investigation show evidence of structural remains consistent with the outbuildings we were looking to find.

In search of Ayr Mount's supporting structures, a team from the University of North Carolina surveyed an 11,000 square-foot area.

These findings are important in several ways. First, this is the only tangible evidence we have so far about the workspaces that provided the daily necessities of food and water to the household. In addition, these spaces were built for and used exclusively by the enslaved people who provisioned the Kirkland family. Finally, buildings like kitchens were also dwelling places where enslaved people not only labored, but also lived. We know that this kind of information is vitally important to helping us provide the fullest interpretation of historic homes and their histories. Ground penetrating radar is not wholly conclusive—it only tells you that something is there, not what that thing is. We cannot know for certain what is underground without digging down to see. Fortunately, GPR results can help archaeologists make targeted excavations that minimize disruption to a site while still revealing important discoveries.

Preliminary results from this investigation show evidence of structural remains consistent with the outbuildings the UNC team and the Jenrette Foundation were looking to find.

As our university partners continue to analyze the data they collected, we expect to learn more about the many layers of Ayr Mount’s past.

Projects like this are yet another way the Jenrette Foundation supports educational opportunities for students who are training for professions in the field. See how these experiences impact the students–in their own words–on our YouTube channel.